Many anti-choice people out there try to claim that the bodily autonomy argument is extremely faulty and easy to take down, which usually results in half-assed and very weak rebuttals to the argument. It seems as though they think that if they pretend there is no weight to bodily rights, they don't really have to argue it very well. If anti-choice people are honest with themselves and everyone else, however, they admit that the argument for a woman's bodily autonomy is strong, and work within that premise to take it down. These rebuttals tend to be much stronger than the former.

Still, I have yet to hear a single rebuttal to the bodily rights argument that is not, at its core, deficient. Some of them misunderstand what bodily autonomy means, while others make huge assumptions regarding a woman's right to autonomy. This post will be dedicated to unpacking each one of these arguments and showing why, at the end of the day, there isn't an anti-choice argument out there that sufficiently comes out as stronger than the bodily rights argument.

Below, I've outlined the most popular responses to the bodily autonomy argument. If you discuss abortion with someone who is anti-choice, you are likely to hear at least one of them (especially if you've geared the conversation toward bodily rights to begin with).

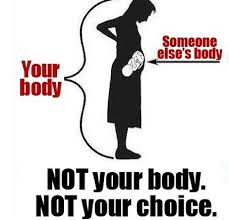

1) It's not your body! There is another body at stake and it's completely separate from yours.

This is a common argument that anti-choicers respond with when a woman says, "My body, my choice."

They say, "Nope, not your body -- it's someone else's body and you have to leave it alone!"

This is a misunderstanding of the argument. Nobody is saying that the fetus is a part of a woman's body, and she should therefore get to do whatever she wants with it. What she is saying is that because the fetus is housed inside of her body, she gets to decide whether or not it stays.

Terminating the pregnancy and removing the fetus from her body is the point -- getting to either allow or not allow a fetus to remain inside of her body. That's what women mean when they say, "My body, my choice."

With that understanding, it's interesting to look at the above graphic because it completely admits that the body surrounding the fetus is the woman's body. What they fail to understand here is that because that body is hers, she doesn't have to allow the body that isn't hers access to it.

2) You made your choice when you had sex. We know where babies come from. If you consent to sex, then you need to be responsible for a possible pregnancy.

This is probably the most common anti-choice response to the bodily rights argument. As soon as you bring up bodily autonomy, I can almost guarantee that, most of the time, the next thing out of an anti-choicer's mouth will be some rendition of, "Women put themselves in the position of having a dependent fetus in her body. She already made a choice by having sex."

The problem here is that, as Matt Dillahunty once pointed out in an abortion debate, consenting to sex does not mean one has consented to pregnancy, and even consenting to pregnancy does not mean one has consented to remain pregnant. Women have a right to consent to sex without consenting to pregnancy, and women also have a right to revoke consent to their bodies at any time (just as anyone else does).

Being stripped of ownership over one's body is not a just consequence for consenting to sex, and there is absolutely no comparable application of law in this country (the United States). In other words, there is no other instance in which the government can force someone to donate their body to someone else simply because they caused them to need their body. Understanding a risk does not mean that someone should then have to suffer extreme consequences, such as losing their bodily rights.

As Tracie Harris put it, "The idea that understanding risk means that you must suffer through any result that occurs with regard to anything you do, without remedy or without capacity to mitigate those risks, is ludicrous. ... Simply pointing out a person understands a risk of an activity is not an argument for saying they must suffer through any consequences, including bodily injury and death, without access to help if the risk event occurs and they end up in a dangerous situation. And pregnancy is a dangerous situation. ... We don't get to force someone to take on risk of ... harm and death simply because 'you had sex' or even 'you know sex can cause pregnancy.' When someone engages in perfectly legal activities -- like sex -- they absolutely do not lose any rights, nor is there any reason they should lose the ability to seek help to protect themselves from further harm if that is the course they choose."

Consider a father driving his daughter to a birthday party. He's not paying attention and causes an accident, through which his daughter then needs a blood transfusion from him in order to survive. Would the man likely donate his blood? Probably, but that's not the point. Can the doctors strap him down and force him to donate blood, just because the girl is his daughter and he caused her to need his body for survival? Absolutely not, because that would be a violation of his own bodily autonomy. It doesn't matter that he knew having a child might cause his daughter to one day need his body, and it doesn't matter that he knew driving a car with her inside posed a risk to her.

Do we really want to live in a world where, if you somehow cause someone to need body parts -- even if that wasn't your intent -- you're then legally required to donate them?

In short, it is extreme to suggest that every time a woman has sex she must also consent to give up ownership of her body to someone else who might need it. Such laws simply do not exist in our country for any other situation, and this one in particular would negate equal and fair treatment of all women (the notion that women's bodies belong to other people as soon as they consent to sex requires women to take on the role of second-class citizens).

Further, the "you shouldn't have sex unless you're ready for a child" argument is hypocritical at its core, and this becomes clear when discussing the ever-popular rape exception. Here's why:

If an anti-choicer does believe in rape exceptions, then their "pro-life" advocacy has nothing to do with babies and everything to do with controlling women's sexual freedom. Babies conceived through rape are still babies. If someone wants to outlaw abortion, but has a soft spot for women who have been raped, what they're really saying is that they think women who consent to sex should be punished by being stripped of their bodily rights, but if women didn't actually choose sex, then they can certainly have their rights recognized. This stance is all about punishing sexually active women (which is crystal clear when people use phrases such as, "keep your legs closed" when discussing reproductive rights).

In short, our laws do not require people to give up their bodily rights to anyone for any reason -- we don't even require body donation from violent criminals in prison or dead people who don't need their bodies anymore -- so requiring women to do so just because they chose to have sex isn't at all justifiable. Many women have sex for other reasons than procreation, and they shouldn't be required to fully endure a pregnancy just for choosing to engage.

3) Bodily autonomy is not absolute. You can't go outside naked, have sex in public, or do lots of other things with your body. You therefore can't do whatever you want with your body!

This argument comes from a complete misunderstanding of bodily autonomy. It also relies on the notion that women who seek abortions are using their bodies in an exercise of force on another body, rather than acting in defense of their own bodies.

Bodily autonomy is having ownership over one's body. It means that no one else owns you, and no one else can use your body for their own sake. This concept is why slavery and rape are illegal -- you cannot own, or claim ownership over, any other human being.

The government can still create laws for societies. Saying that I cannot be naked or have sex in public is not claiming ownership over me; rather, it's setting up a blanket rule for what's allowed in public places (and I can, mind you, be naked and have sex in private places). Everyone must abide by these laws, and, again, they have nothing to do with stripping me of rights to myself.

Telling me, however, that I must allow a parasitic relationship to complete itself inside of my body when I don't want that to happen would be violating my personal bodily rights. Forcing me to have sex would be violating my bodily rights, and forcing me to donate blood or organs would also be violating those rights. There is a big difference between having to abide by societal rules while in public and being forced to allow someone else access to your body.

It's important to understand that difference, and to understand what bodily autonomy truly entails.

4) Bodily autonomy is not absolute. Look at the case of conjoined twins -- both twins have to share their bodies, and the dominant twin cannot simply order the other one to be killed because they don't want to share their body anymore.

When arguing this point, anti-choicers will often discuss the true story of Mary and Jodie, a set of conjoined twins from Britain who created a controversial case when a court ordered the twins separated even though they knew that separation would cause Mary to die. You can click the link to read the whole story.

Anti-choice advocates argue the ethics of these decisions and compare them to abortion and the claim of bodily rights. They think that the murky waters of conjoined twin cases presents a clear-cut case that bodily rights are not absolute, and therefore a weak argument for abortion rights.

But here's the thing -- the two are not at all comparable (and this is true no matter what decision is made in terms of the life or death of a conjoined twin). The major difference is that conjoined twins that are dependent on each other are not born with bodies of their own; rather, they are born sharing their bodies with someone else, which makes the bodily rights claim debatable in these instances. Which conjoined twin actually owns the conjoined body? In truth, they both do, and that is the case from birth.

A pregnant woman's body, on the other hand, did not originally have a fetus inside of it. She was not born sharing her body, and the fetus is therefore much more of an invading presence than a conjoined twin.

I am not arguing here for or against the ethics of separating conjoined twins. What I am pointing out is that it is an entirely separate issue from abortion, and not comparable. In the case of conjoined twins, it can be debatable whether they are entitled to each other's bodies because they were born sharing one body that didn't fully split. Both twins arguably have rights to the body in question, because that body is, quite literally, both of theirs. But a fetus is never entitled to use a body that does not belong to it. A pregnant woman was born with a body of her own that she then chooses to share with a fetus at some point in her life (or not). Because she's had full ownership over her body from the time she was born, she has every right to deny anyone access to it.

The comparison, then, between twins who have always shared one body and a woman who finds herself pregnant is extremely faulty.

5) You can't call abortion "self defense" because abortion involves the deliberate killing of a baby. Unplugging from a violinist (per Jarvis' original argument) is very different than actively killing someone.

When you point out that everyone has bodily rights, and that no one is forced to donate their bodies for the sake of others, anti-choicers are usually quick to argue that allowing someone to die by denying them blood or organs is natural, but abortion is an active act of killing someone, which makes it different.

As I pointed out in Part 1, anti-choicers have been very successful in painting abortion as the deliberate killing of a baby -- they frame it as a murder rather than the act of ending a pregnancy. Their mental images, however, of cut-up babies doesn't at all reflect the reality of what abortion entails. Abortion is the termination of a pregnancy -- the removal of an embryo or fetus from a woman's body -- but said embryo or fetus can't survive without the woman's body, so it usually dies. A viable fetus close to full-term can be delivered and survive, but a non-viable embryo or fetus cannot. Thus, it's fair to point out that removing a fetus from a woman's body, knowing that said fetus will then die, is not all that different from denying someone a body part knowing that they will die without it.

This is all about understanding that, once again, abortion is simply the termination of a pregnant state, after which a fetus usually cannot survive.

6) Pregnant women have a special obligation to their unborn children. The relationship between a pregnant woman and the baby is significant.

In response to bodily rights, anti-choicers will sometimes claim that a woman has an obligation to carry a pregnancy because the life that hangs in the balance is her child. They argue that it's a completely different situation from Jarvis' violinist scenario because that "special" relationship doesn't exist like it does with a mother and baby, and parents have obligations to keep their children alive and healthy (whereas they do not have an obligation to keep strangers alive and healthy).

The first thing to point out is that many women do not have a special bond with an embryo growing inside of them, and it's not anyone else's business to decide that such a relationship -- or obligation -- needs to exist. I don't consider the 6-week-old embryo that I removed from my body to have been "my child," even if other people do.

The other problem with this assumption is that it does not extend to babies who are already born. Anti-choicers claim that women have a special obligation to offer their bodies up to growing fetuses ... but, once that baby is born, any bodily obligation of parents mysteriously disappears. If women have an obligation to allow a fetus to gestate, why don't they (and the men involved) have an obligation to donate blood or body parts to their born children? Why aren't they required to put their bodies at medical risk in order to save the lives of their children? The fact that the "parental obligation" argument is not applied once the baby is born (at least not in terms of having to give up bodily rights) is highly suspicious, and clearly a sign that people who argue from this perspective actually want to burden pregnant women with obligations not required of other parents, and grant rights to fetuses not enjoyed by children who have been born.

7) If you weigh losing nine months of bodily autonomy against dying, it's clear that the baby's right to life should outweigh only nine months of bodily autonomy.

This is a hugely dangerous precedent. If we follow through with this line of thinking, and apply it across the board (not just to pregnant women), what's to stop the government from mandating bodily donation in a variety of instances?

You have blood type O, the universal blood type? Well, hospitals need more of that, so you have to donate -- a needle, fatigue, and a small amount of your personal time are not relevant when weighed against other people dying. It doesn't matter if you don't want to donate -- it's the law, because other lives hang in the balance.

Or how about the fact that we all have two kidneys? We can donate one of those, since there are so many people who need one. Oh, and after you die, you must donate your organs to those who need them. Any medical procedure, or cutting up your body after you're dead, are not relevant when weighed against someone else's life. So, by law, you must agree to this.

It's scary to think about what the world would look life if your bodily autonomy was weighed against other people's lives, if you apply the concept across the board. And if you wouldn't apply it across the board, then why would you subject pregnant women to this mentality (particularly when pregnancy is neither short, nor easy, nor risk-free)?

8) A developing baby is in its natural state in the womb. It is, therefore, entitled to stay there for as long as it needs. It's the natural order of things.

This premise assumes that the woman's body doesn't fully belong to her. It assumes that, each time she's pregnant, her uterus and nutrients "naturally" belong to a growing fetus. It's the fetus' body, first and foremost, if the woman is pregnant. Can you see how dehumanizing that thought process is?

If you've ever taken a course in logic, you're probably aware of the Naturalistic Fallacy, the premise of which assumes, "X is true, according to nature; therefore, X is morally right." This is a logical fallacy that presupposes that just because we think something is "natural," that thing ought to be the norm, or the way we approach something.

There are lots of "natural" things in this world that we alleviate through "unnatural" means. Eyeglasses are an unnatural response to the natural state of eyesight deficiency. Cancer treatments are also unnatural, whereas cancer is a completely natural occurrence. The idea that something is good simply because it's natural or biological isn't a logical stance to take.

Once again, this logical fallacy used in this particular argument assumes that the woman's body doesn't fully belong to her -- it assumes, rather, that there are times when parts of her body belong to developing fetuses instead. It's important to remember that a woman's body belongs to her at all times.

9) Men have to pay child support. Everyone has to take care of their children once they're born. It's okay to expect, then, that women must also provide support before children are born.

As I pointed out in Part 1, it's important to remember the difference between property rights and bodily rights, and it's also important to remember that financial support is not a "man" or "father" thing, but required of all parents.

Men have to provide financially for their children, but so do women. Men have to provide food, clothing, and shelter for their children, but so do women. Men have to keep their children safe from harm, but so do women. If men have custody of their children (which, despite common claims to the contrary, they often obtain if they pursue) then women have to pay them child support. Child support, or financial support of any kind, is not limited to men -- that's a parental thing.

But bodily support is never required of parents. Once children are born, both men and women are free to deny bodily support (think blood or organ donations), even if their children cannot survive without it. This is a clear demonstration that there is a huge difference between property rights (meaning, rights to finances and other forms of property) and bodily rights (meaning, a parent's right to their own bodies).

Therefore, again, requiring pregnant women to donate their bodies is not on the same level as financial support (again, required of men and women) for children, especially when such support is not required of parents after a baby is born.

10) A woman has a right to control her own body only until she's harming someone else. Her right to "swing her arm" ends when she harms the fetus inside of her.

Actually, this isn't true. Self-defense laws insist that a person can harm another if the are defending themselves. This argument is akin to saying that someone must allow a rapist to rape them if stopping the rape would mean harming the rapist. Your right to swing a defensive "arm" never ends just because that arm might hurt someone else.

But this, again, assumes that the body in question belongs to the fetus. It doesn't. It belongs to the woman.

The phrase above, then, is better stated as, a fetus' right to exist (or, as Matt Dillahunty once put it, "swing its umbilical cord") ends when a woman decides she doesn't want it in her body.

If a woman has rights to her body, she has a right to evict an unwanted tenant. If that right ends before she's allowed to do that, then she does not have ownership over her own body.

11) If this is about bodily rights, then how could you restrict any aspect of abortion or disapprove of abortion at any stage of pregnancy? Obviously, this idea is not consistently applied.

But it is consistently applied -- many people simply don't pay attention to that fact.

From a bodily autonomy perspective, women should be allowed to end a pregnancy at any time. Sometimes that results in the death of an embryo or fetus. But if the fetus is viable, it can result in a live delivery. In such a way, it's easy to see how abortion can certainly be consistently applied at any stage of pregnancy.

The problem, which I've mentioned quite a few times now, is that anti-choicers don't see that abortion is ending the state of being pregnant -- as, quite literally, aborting a pregnancy. They see it as murdering a child, with the desired outcome being the death of a baby. So, to them, the idea of abortion is married to the idea of killing babies. If they understood that aborting a pregnancy when a fetus is viable can result in a live birth, they'd likely see things much differently.

For example, my own labor was induced nearly three weeks before my due date because of severe health problems. This was an abortion -- my doctors and I aborted my pregnancy before it was "naturally" ready to be done. The result, however, was the live birth of my son.

Anti-choicers are fond of discussing bans on late-term abortion, but if they understood the nature of abortions (and applied their logic consistently), they would be more interested in banning early abortions because early abortions always result in the death of an embryo or fetus. Late term abortions can result in the same thing, but don't always. Anti-choicers need to be reminded that their mental images of cutting up eight-month-old fetuses for the sheer pleasure of it are not based in reality.

(As a side note, late-term abortions are nearly always done because of health issues in either the woman or the fetus, or, sometimes, because women have not been able to access an abortion earlier due to strict anti-choice laws in her area. Women honestly don't wake up one morning eight or nine months pregnant, have breakfast, and decide out of the blue to go have an abortion. It really doesn't work that way. So bans on late term abortions almost always affect people who are already going through extreme amounts of grief. People's medical issues are between them and their doctors -- as a spectator, it's really the most ethical thing to stay out of it.)

12) Who said you had a right to bodily autonomy, anyway? You need to prove why this right exists, and then why this right should be applied within the context of pregnancy, before you can use it to keep abortion legal.

Actually, the reverse is true.

As Matt Dillahunty once said, in a debate with secular anti-choicer Kristine Kruszelnicki, "When it comes to determining what sort of rights we're going to grant people, there are two primary methods. The first is that we begin with no rights, and are free only to exercise the rights that we specifically enumerate. The second is that we begin with all rights, except for those that we specifically limit. The first option is patently absurd -- where did you get the right to begin defining rights in the first place? The second requires that we focus our attention on how and why we're going to restrict certain rights. Which rights take priority, and what do we do when rights come in conflict? The right to bodily autonomy is one of the most foundational principles that has guided this process. When a proposed restriction would violate this right, there is a very heavy burden to overcome before that violation could be justified."

In expanding on this, I'll repeat that our society recognizes a foundational right to bodily autonomy -- it is the basis of individual freedom. If you do not own yourself, then by necessity, someone else does (in the case of criminalizing abortion, a fetus would be grated legal access to a woman's body without her consent, and the government would, in part, also claim ownership over a pregnant woman's body in order to enforce the law). You simply cannot have freedom without ownership over yourself.

It's actually, then, the anti-choicer's job to justify why denying bodily rights to pregnant women alone should be permissible. Again, we already recognize bodily autonomy in every other instance, so the burden of proof falls on those who think that this right should be limited in this one circumstance -- why a woman should legally lose control of her body when she's pregnant. A right to bodily autonomy is vital to freedom, which is highly valued in our society, so this burden of proof -- as to why a woman's personal freedom should be severely limited when she becomes pregnant -- requires high levels of justification. Denying women this basic right is making women slaves to their biology.

13) Your body isn't yours. It belongs to God. Or, by way of biology, it belongs to fetuses sometimes. It's just the hand you were naturally dealt.

Interestingly, anti-choicers don't often apply this logic to other people -- they don't actively argue that people's bodies don't belong to them. This idea seems to be limited, exclusively, to pregnant women.

The one exception is when religious people argue that we all "belong" to god(s), and we therefore must submit ourselves to whatever happens to us through said power(s). People are free to believe this, but because we live in a secular nation, they cannot cement it in law. I don't believe in any gods, and cannot be forced to act like I belong to a deity that doesn't exist. So while people may argue over the morality of abortion because they "belong" to a god, that argument cannot and should not impose on my life in any legal manifestation.

In short, claiming that women simply shouldn't have bodily autonomy because of biology or shared bodily ownership is blatantly sexist and antithetical to freedom and equality under the law. Women should not have to give up personal rights simply because, through biology, we have the capacity to become pregnant. Either we recognize the rights of women as individuals, or we don't -- and to limit a woman's right to bodily autonomy suggests that we don't. And I would question anyone's loyalty to "freedom" if they think biological slavery is acceptable for half the population.

14) I have never heard anything so selfish in my entire life.

Maybe arguing for one's consistent rights to their own bodies is selfish. Maybe it isn't. Maybe said selfishness is a bad thing. Maybe it isn't. It doesn't really matter, nor should one's own definition of "selfish" be the basis through which we legislate people's rights.

The bottom line is that if you've come this far in the argument, and an anti-choicer is accusing you of selfishness (or trying to invalidate your argument simply because they think it's selfish), you've won. They have run out of arguments to use to try and justify denying women legal bodily autonomy, so they're instead turning to personal attacks.

Congratulations.